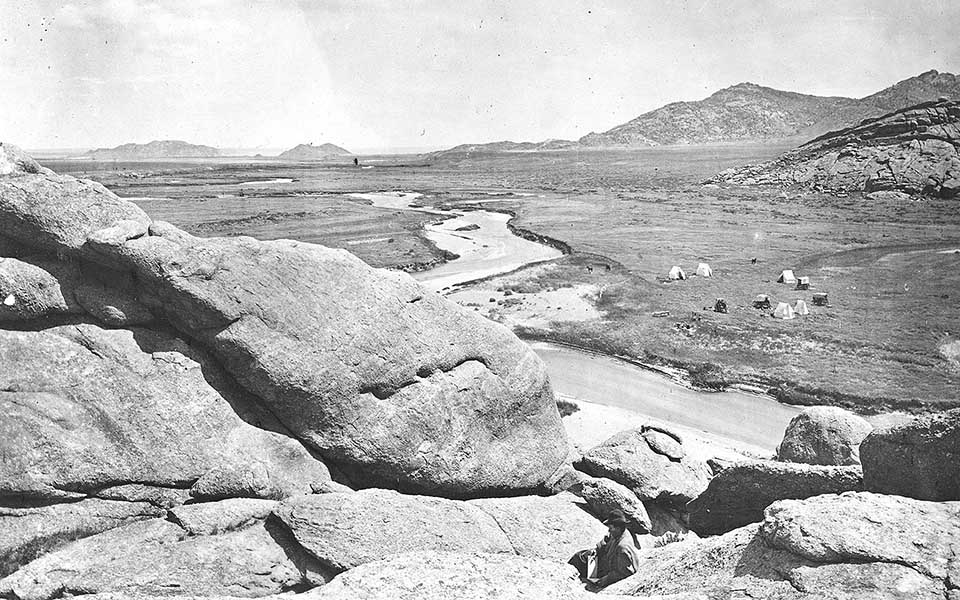

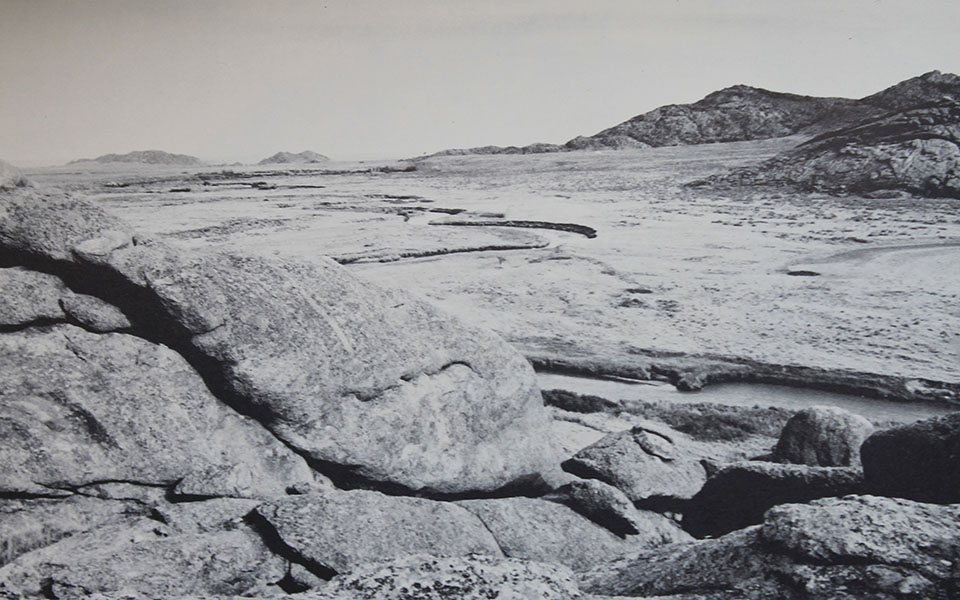

The view east from the top of Independence Rock in 1870 (William Henry Jackson, USGS-jwh00284), in 1976 (K. L. Johnson 7-141), and in 2016 (CW-2016-06-18-0355).

America’s Great Travel Corridor

In the fall of 1812, Astorian fur trader Robert Stuart and 3 fellow companions crossed the continental divide, and trudged eastwards down the Sweetwater River, passing what would become known as Independence Rock on October 29th. They were returning to the then boundaries of the United States from their trading fort on the Pacific Ocean to report to owner Jacob Astor of the trading mission’s impending failure. Like many stories of the Astorian venture, their trip east appeared to be ending in disaster– Crow warriors had stolen their horses on the western slope of the Rockies, they had walked hundreds of miles in a circular path to avoid further attack, winter was coming, and they were short on food.2 But their luck had turned, and they were now passing along a corridor that for many thousands of years had been a great travel route across the Rocky Mountains for bison and their predators. Important to the fate of Stuart’s party as they moved eastwards into the impending winter was that they were approaching an area of bounteous buffalo along the Sweetwater and North Platte rivers. These great herds were the source population for bison dispersing westwards on to the Pacific slopes. Their high numbers along the North Platte may have been the result of being in an inter-tribal buffer zone between the Shoshone to the west, Crow and Cheyenne to the north, Pawnee to the east, and Arapahoes to the south.3 A few days later the fortunate Astorians would be fully stocked with bison meat, and wrapped in buffalo robes within a shelter of shelter of hides to protect them from winter winds and snow.

A few decades later, the deep buffalo trails they walked along in the gently-sloped, grassy valley of the Sweetwater River would be followed by thousands of Americans taking covered wagons across South Pass along the Oregon Trail. The great travel corridor would ultimately help shape the continental territory of the United States.4

Footnotes and Map

- Johnson, K. L. Rangeland Through Time: A Photographic Study of Vegetation in Wyoming 1870–1986. Miscellaneous Publication 50. Laramie, WY: Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station, 1987. ↩

- Rollins, P. A. ed. The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Narrative of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812-13. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935. Republished Lincoln: University Nebraska Press, 1995. ↩

- Hodge, A.R. “Adapting to a Changing World: An Environmental History of the Eastern Shoshone 1000-1868.” Ph.D. diss., Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012. ↩

- Bagley, W. South Pass: Gateway to a Continent. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014. ↩